Vaccines are biological preparations that, when injected, simulate an encounter with the infectious agent as if one had come in contact with the natural infection but without causing the disease or its complications.

The efficacy of vaccines is based on our immune system's ability to create memory cells that remember which foreign pathogens have attacked our bodies.

These cells allow an immunological response to occur much more rapidly than in an initial contact with the infectious agent, thus preventing the pathogen from harming the organism while the organism produces an adequate immune response, a task that could take up to several weeks.

The history of the discovery of vaccines began in 1796 withEdward Jenner, an English physician, who noticed that milkers who contracted smallpox from cattle, and subsequently recovered, did not become ill with human smallpox.

He then tried to administer a boy, James Phipps, with material from a bovine smallpox pustule. Six weeks after that administration, he infected him with the human smallpox virus, and what he noticed was that, as he had anticipated, the young man did not develop the infection.

The young man did not develop the infection.

Edward Jenner was thus the first to successfully experiment with a vaccine, and the idea of using animal viruses to counter human diseases has continued to the present day.

The idea of using animal viruses to counter human diseases has continued to the present day.

He was also the one who coined this new meaning of the word vaccine to describe his discovery; in fact, the etymology of the word vaccine is derived from the Latin adjective vaccinus, which means cow derivative.

His work began a long journey that enabled the eradication of cow, officially announced during the thirty-third World Health Assembly on May 8 1980.

The next most important discoveries in vaccination, after Jenner, were made some sixty years later in 1855 by Louis Pasteur.

He noticed that rabbit poultry infected with the rabbit virus were no longer infected after about 15 days of drying.

Thanks to this discovery, with a series of inoculations with suspensions of dried rabbit spinal cord, Pasteur saved the life of Joseph Meister, a nine-year-old boy who had been attacked by a rabid dog.

Pasteur thus paved the way for the creation of vaccines containing viruses rendered inactive through chemical or physical processes.

The term vaccine, initially used only to refer to that of smallpox, was extended by Pasteur to all vaccines to describe his success and honor Jenner's pioneering discovery.

Through the strategy of inactivated viruses during the 20th century, several vaccines were created, including the influenza vaccine made by Thomas Francis in the early 1940s, the polio vaccine obtained by Jonas Salk in the mid-1950s, and the hepatitis A developed by Philip Provost and Maurice Hilleman in 1991.

The next advance in the world of vaccines was by Max Theiler who in the 1930s succeeded in attenuating the yellow fever virus, a human virus, by growing it in mouse and chicken embryos. In this way, the virus was unable to cause the disease but could induce protective immunity in those who received it.

This insight of his inspired many others to develop vaccines with live attenuated viruses; most notably Albert Sabin, trained in the same laboratory as Theiler, created a new polio vaccine in the early 1960s using monkey cells.

Subsequently, again using this technique, the vaccine to prevent mumps (1963), the one for mumps (1967), the one for rubella (1969), the one for varicella (1995), and the one for rotavirus (2008) were created.

A further breakthrough came in the 1980s when Richard Mulligan and Paul Berg, two Stanford biochemists, were able to make mammalian cells produce, through DNA modifications, a bacterial protein.

This discovery applied in the field of vaccines allowed for the development of the hepatitis B vaccine (1986) and the human papilloma virus vaccine (2006).

Thanks to all these discoveries, it has been possible to reduce mortality from many diseases, for example, the use of the vaccine devised by Sabin, polio vaccine, has led to the eradication of wild type 2 and wild type 3 poliovirus from five of the six World Health Organization regions (Americas in 1994, Pacific Region in 2000, Europe in 2002, Southeast Asia in 2014, and Africa in 2020, while polio is still present in the Eastern Mediterranean areas); the rubella vaccine brought the number of rubella cases worldwide from 671.000 in 2000 to 49,000 in 2019, and so have many other vaccines.

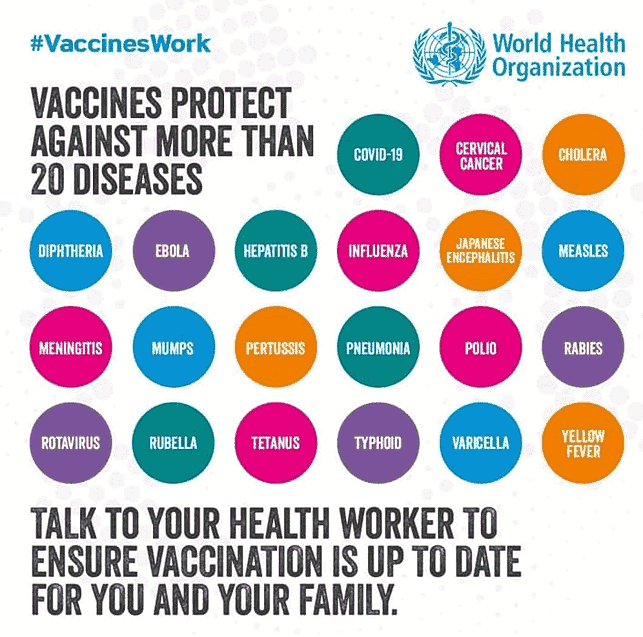

To date, several types of vaccine have been developed:

- live attenuated vaccines as in the case of measles, rubella, mumps, varicella, yellow fever, and tuberculosis in which the microorganisms are weakened by appropriate treatments and laboratory procedures;

- inactivated vaccines such as for hepatitis A or polio, in which viruses or bacteria are killed through exposure to chemicals or heat;

- vaccines created from purified antigens (molecules that can be recognized by the immune system) as is the case for whooping cough or the anti-meningococcal vaccine in which, through various laboratory techniques, certain bacterial or viral components are purified;

- vaccines with anatoxins as in the case of tetanus and diphtheria in which the toxins produced by these bacteria are made safe, capable of activating the body's immune defenses but not causing disease;

- recombinant protein vaccines, e.g., hepatitis B and meningococcal B vaccine, in which, through recombinant DNA technology, the genetic material of a microorganism is modified in the laboratory so that it produces the necessary antigen that will then be collected and purified for inoculation.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, finally, a new and advanced technique for vaccine production was introduced: that of mRNA vaccines.

With this technology, a segment of mRNA from a virus fuses with human cells and temporarily initiates the production of a particular protein (Spike protein). This protein is recognized as foreign by our immune system, thus stimulating the production of antibodies.

Given the importance of vaccines in maintaining public health, it is essential to monitor the degree of vaccination coverage of the population.

Italian vaccination coverage data for the year 2021 report an overall improvement in coverage of most of the recommended vaccinations in the early years compared with data collected in the previous year (2020).

This figure is very important and reflects the work done by regions to increase vaccination campaigns after a period of declining coverage due to the COVID-19 pandemic that impacted routine vaccination activities.

Reaching a vaccination coverage threshold of 95% of the population is essential to limit the circulation of pathogens in the community and achieve population immunity in addition to protecting individuals.